Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame awards

Nov. 17, 2025. We were recently honoured with ‘legends’ awards for two of our earliest songs, Talk to Me of Mendocino written by Kate and Heart Like a Wheel by me. Rufus and Martha sang a very moving version of Mendocino, augmented by a string quartet. Then Sylvan and Lily joined them for an equally beautiful Heart Like a Wheel. Also that night, a complete surprise, the Montreal trio Le roy, la rose et le loup did Complainte pour Ste-Catherine, a song I wrote early on with Philippe Tatartcheff. It was really good. I hope they record it! There were sincere heart-warming compliments from Emmylou Harris, Judy Collins and Linda Ronstadt. It was a ‘perfect’ night. Thank you all for this and sorry to be so late posting this.

4 Comments »

Kate & Anna McGarrigle 1976 by Laura Snapes for Pitchfork

9.5

By Laura Snapes

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we look back at a trenchant and heartfelt 1975 classic by two French Canadian Irish sisters steeped in folk tradition.

Instead of a family Bible, Anna McGarrigle once reckoned, the McGarrigle children had their father Frank’s old arch-top Gibson guitar. It was one of the few possessions he brought into his marriage to Gaby Latrémouille in 1935. The French Canadian Irish couple inscribed the body of the instrument with the names of their friends as well as landmark milestones. Their daughters evolved the tradition. Their eldest, Janie, added the names of her friends, but also, as a child of the fledgling rock’n’roll era, “ELVIS.” The second, Anna, added her own icon, although misspelled: “DOUANE” as in Eddy, but also as in import “customs” in French, her first written language.

It was on this instrument that trailblazer Jane, cautious Anna, and the youngest, willful Kate, learned their first chords from Frank, Anna writes in Mountain City Girls, a memoir co-authored with Jane after Kate’s death in 2010. Born in 1899, their father expected them to be able to play for company on the family’s 11 beat-up instruments, among them an accordion left as penance by a local drunk whom Frank brought home one night, to Gaby’s displeasure. He would bribe them a nickel to learn a song by the Gershwins, or the Romantic parlor songwriter Stephen Foster, or Hoagy Carmichael. Gaby kept sheet music for popular ballads and showtunes. The French Catholic nuns at convent school in Saint-Saveur-des-Monts, in the Laurentians north of Montreal, taught them solfège and chorales, and Jane drilled them all in harmony. The girls discovered the Everly Brothers and Joan Baez and, later, blues pioneer Ma Rainey and Bahamian guitarist Joseph Spence. Baez, in particular, became their role model, showing Kate and Anna—a natural double act born just 14 months apart—that a girl’s place in music wasn’t limited to buying the boy rockers Cokes after watching them play. She also imbued them with particular standards for their first instruments. Gifted brand new guitars on Christmas 1961, the teenagers turned up their noses and exchanged them for the cheap nylon-stringed versions that Baez favored.

From there came their first vocal trio, with a girl who’d heard Kate singing at their new school after the family moved to Montreal. Soon after, Kate and Anna became part of the Mountain City Four, a folk outfit that sometimes had up to 10 members. While their stage presence was sloppy, the other members were dead serious about developing their interpretations, playing songs learned from the Library of Congress and Folkways, or those of Bob Dylan. When he went electric, so did they. (Anna was at Newport in 1965, and loved it.) If such great songs already existed, these purists reasoned, there was no need to write more, even—or perhaps especially—if Dylan was turning out new standards at a clip. But when Kate moved to New York City in 1969, as part of a duo with guitarist Roma Baran, she hit the Gaslight and Gurdy’s Folk City and various hootenannies, and discovered singer-songwriters showing off original material. She phoned Anna: We could do this too!

That eager call ensured that Kate and Anna McGarrigle’s names would be inscribed in legend. Anna, at home in Saint-Sauveur with Gaby, sat straight down at the family piano—usually so in demand it was hard for her to get a look in—and wrote her very first song, “A Heart Is Like a Wheel,” about a recent heartbreak. Five years later, the desolate number would become a hit for Linda Ronstadt, and the title track of her album of the same name. But perhaps more significantly, wrote Anna: “Being able to voice my sorrow at that time saved my life.” Though they embraced it casually, the two sisters found a lifeline in songwriting at just the right time. At the Gaslight, Kate hadn’t just discovered songwriting but Loudon Wainwright III, forging the start of a tumultuous, painful relationship that inspired many of her early songs. “He’s the only person I’ve gone up to and said, ‘I really like your music,’” she told Melody Maker in 1976, after their marriage had ended for the last time. “Needless to say, I won’t do it again.”

You could also say that songwriting found a lifeline (not to mention a bloodline) in these two sisters. Their 1976 debut, Kate & Anna McGarrigle, revealed them to be masters of unaffected, direct, desirous lyricism, alive with action and motion. (Melody Maker’s writer wondered if they were “perhaps the Lennon and McCartney of a burgeoning generation of women songwriters.”) The album’s rapturous reception, particularly in the British music press, often characterized it as a record of domesticity. Its rich, weathered but vigorous blend of French and Irish folk, blues, and balladry certainly reflected their music-steeped childhoods, and Joe Boyd and Greg Prestopino’s production made the record glow with all the invitation and protection of a warm hearth. The sisters’ naturally classic way with melody made it seem like families had sung these songs around the piano for centuries already. Their harmonies were so innate that Boyd initially thought that Kate had just multitracked her own vocals on some early demos, and the pair took a nonchalant approach to success, always putting family first. The album’s sleeve thanks the recording studio superintendent for looking after Kate and Loudon’s “little Rufus” (as in, Rufus Wainwright, future dynastic star) during the sessions in 1974 and ’75. Her subsequent pregnancy with Martha (ditto) led them to cancel a tour promoting the album. “I don’t remember us giving much thought to ‘the record,’” Anna wrote, bemused by the idea.

But something about the focus on “domesticity” suggests a shelteredness and dutiful femininity that couldn’t be further from the reality of this expansive album, one that travels far to work out what it means to be home. Kate, said Anna, was “the great escape artist,” someone who saw herself as “one of those people who had to move on, to get out,” who left for NYC to become “the character she wanted to be.” Her early attempts at making it as a solo artist went nowhere—a showcase didn’t work out; Clive Davis passed on her; a dog once invaded her stage during a pitifully attended set—but she managed to get her demo tape in front of Prestopino, who passed it to Boyd and Warner exec Lenny Waronker in Los Angeles. They asked her to play one of the songs from her demo tape on the piano, and couldn’t understand why she didn’t know the chords. Because it was by Anna, she said. Struck by the novelty of two songwriting sisters of apparently comparable talent, they asked them both to come out and record. Kate was bored singing alone and figured it “beats working in an office.” She convinced Anna to quit her job and come to LA. Anna brought her red accordion, and they lived on and off at the Chateau Marmont for nine months, the latest stop on their roaming.

The beauty of the songwriting on Kate & Anna McGarrigle is in how they capture the speed at which love can transform or undo a place, make you feel you belong or spit you out just as fast. The album opens with Kate’s “Kiss and Say Goodbye,” a rollicking tangle of guitar and sax that groove and joust as the youngest McGarrigle obsesses over a prospective lover coming to town. The tune bounces as if she were skipping down the sidewalk, a carnival of one high on hope. She doesn’t know when her man will arrive, but that doesn’t stop her setting the terms. He’s coming her way, not the other way around. He’s only to call her if he’s alone. She knows his type. “I know you like to think you’ve got taste,” she teases, “so I’m gonna let you choose the time and place.” It’s only desire that she can’t bend to her whim. “And I don’t know where it’s coming from/But I want to kiss you ’till my mouth gets numb!” Who needs to see “some foreign film from gay Paris” when Kate McGarrigle can turn a flirty reverie into a full-blown movie? (Yet the Village Voice called the sisters “genteel,” NME called them “spinsters” and Rolling Stone commented on their “puritanical sensibility” and lack of “sexual overtones”: Even glowing reviews could only stand to see these free-thinking women, who freely discussed which other members of their band they had slept with, in half shadow.)

If “Kiss and Say Goodbye” overspills with potential, the next song, Anna’s “My Town,” has been gutted of it. It’s a quivering waltz of piano and mandolin with shades of “Moon River,” stoic and swooping as Anna reckons with heartbreak stealing her home away. “It’s my town but I had to leave it,” she sings with painfully bright acceptance, though she doesn’t spare the cad that loved her under false pretenses. One night, she walks past his house. “The lights were on to ward off thieves/While you stayed out all night/But it was you who stole my heart/When you hadn’t any right,” she sings, and a harmonica turns her tapering line into an old-timey lament. Kate’s harmonies cushion her words, but nothing can soften their brutal economy.

It’s funny that “Heart Like a Wheel” is the best-known track from this album. Anna mixes her metaphors—love is also “like a sinking ship”—and later called it “an awkward little song,” although its pearlescent tragedy, featuring organ by Janie, is anything but. The sisters’ real lyrical stock-in-trade is fierce straightforwardness without sentimentality: a marvel, considering the difficult background to Kate’s songs. 1971 proved a dismal year. She was married to Loudon, who was unfaithful. (He claimed that neither of them were “domestic.”) She cried while recording “Go Leave,” just like Anna and their friends back in Montreal had cried listening to her demo. Even the finished recording is the starkest ballad, one of curtains-drawn insularity: just her nylon-stringed guitar, heavily thumbed, offering a slight foundation for a vocal performance of the purest poise, as defeat—“she’s better than me”—begets defiance. She holds the elegant vibrato that prolongs the end of some lines like a meditation, a precise focal point to keep darker feelings from intruding. But for all her resolve, she can’t avoid one nagging question: “But could it be that you are stalling?/Hearts have a way of calling when they’ve been true.” There are few songs more incisive on the hope you’re willing to invest in somebody who has already squandered a great deal of it.

Kate’s year would worsen. Loudon did stall, and soon they were living in London and expecting a child. She miscarried around six months, a boy named Jack. “The infant boy had made a little squawk then been whisked away,” Jane wrote. Loudon left Kate again, leaving an expensive blue Volvo and a banjo as penance. In “Tell My Sister,” home shifts once again, from “England in the pouring rain” back to Montreal. She can’t bring herself to tell Gaby she’s coming back, so instructs Anna to do it, pulling baby-sister rank. The lilting woodwinds sidle around her furtive verses, as if a little shame-faced. It takes halfway through the song for the instruments to spill over into easy ceremony, giving in to welcome without question and finding at least one definition of home. A few bawdy brass refrains hint at her desire to break free again: “But until then, tie me to the ground,” she sings, knowing she can’t be trusted to act in her best interests. “I’ve got to let these weary bones rest/From all that runnin’ around.”

She would run again. Kate met a fisherman and fiddler named George “Smoke” Dawson. He taught her how to play in a droning style, and they got together for a time and drove out west. And yet “Talk to Me of Mendocino,” his California home, is almost as devastating as “Go Leave.” There is something of “Both Sides Now” to its grievous serenity, as it becomes an elegy for the dream of stability: “Let the sun rise over the redwoods/I’ll rise with it ’till I rise no more”—a vision that you can tell feels impossible as she sings it. Kate’s lower voice is crushed. Anna’s hymnal brightness lends her dignity. A distant accordion doubling their melody takes over to carry their lament. Loudon came back.

Maybe Kate & Anna McGarrigle has taken on its domestic reputation because—like Carole King’s Tapestry, a record it fairly equals—it feels like a place where anyone can go to recover from their troubles. The instrumentation swells with care, warmth, wisdom—the great weft of influence, experience, history that makes up a life, that reassures you that you’re never the first to feel this way. (As teenagers exploring the new folk pop scene, Kate and Anna were more interested in searching out the source material that inspired these new stars: For the sisters, with their familial legacy, these traditions seemed eminently present.) For all the romantic desolation in its lyrics, Kate & Anna McGarrigle is ecstatic about its influences. It travels even further than its protagonists do, from the clarinet-led New Orleans blues of “Blues in D,” in which Kate gives in once again to a returning Loudon, to the Cajun fiddle and accordion fleck of “Complainte Pour Ste Catherine,” Anna’s in-jokey portrait of the morés of Montreal’s main street. “La gloire, c’est pas mal inutile,” they sing: Fame is pretty useless. Their rambunctious French singing and downhome pride almost evokes the Raincoats’ glorious raggedness; the song even climaxes in a brassy, funky precursor to punky reggae.

The closing song is an interpretation of the Bahamian spiritual “Travelling on for Jesus,” which might feel a bit out of place: The sisters’ songs never look to God for succor, and the adult Kate once suggested a school nun who reached out to make amends should “go fuck herself.” But its message of forgiveness and knowing one’s own mind as the keys to carrying on rings true, and its inclusion feels characteristically wry. (It’s a more openhearted version of the message than their cover of Loudon’s “Swimming Song,” an appealingly brisk fiddle and banjo number about staying afloat in life out of sheer spite, and cannon balling to splash the haters while you’re at it.) Kate & Anna McGarrigle carries a strong sense of what matters: family; home; love, no matter how many take its name in vain. “Foolish You,” a song by local musician Wade Hemsworth that they covered in the Mountain City Four, rebukes a lover for going away, “seeking fortune’s favor on your own.” What makes it worth leaving? Why do something alone when you could do it together and be “interlocking pieces,” as Anna puts it, in her lovely “Jigsaw Puzzle of Life”? (You could write a whole essay on how they make an art form of the word “fool,” about themselves and others, buoyant with understated disappointment. Loudon wrote “Red Guitar” about him smashing and burning his Gibson in the Saratoga Springs flat he shared with Kate in 1970: “It burned until all that was left was six pegs and six strings/Kate, she said, ‘You are a fool, you’ve done a foolish thing.’”)

The integrity of Kate and Anna’s debut bore out in their refusal to capitalize on critical acclaim, or to trade on their values. The Village Voice’s Geoffrey Stokes, commenting in a “Fifth Estate” news report, got it dead wrong, saying that their “familial, sloppy, warmhearted, gummy” act “may not make it in a time when one is used to dry ice and proper rhythms.” It was voted Melody Maker’s album of the year, The New York Times’ No. 2 behind Songs in the Key of Life; it reached No. 5 in the Pazz and Jop critics’ poll, and Boyd later called it one of the best albums he had ever worked on. Even the “skin magazines” wanted in: The sisters turned down Playboy and Gallery, although Anna was tickled by the idea they might make the latter’s centerfold, “bound in 16-track tape!” Kate even surmised that Loudon’s final exit, in 1976—for Suzzy Roche of the Roches; you might say he had a type, at least musically—was born of jealousy for their success. “He was at a point in his career when he was frustrated, while my sister and I had made a record that was being touted as the best thing since sliced bread,” she told The Sunday Times in 2004. (Rufus has said his first memory is his mother packing the car to return to Montreal after their final parting.)

Not that they seemed affected by the praise. A single date in London won raves for their endearingly shambolic performance. Still, they canceled a U.S. tour not just owing to Kate’s pregnancy with Martha, but because of their anxiety over having to put together a professional touring band (the label’s suggestion that they wear long skirts and frilly shirts was laughed off). “If people from the record company, or the agency, or whatever, try to get us to be tighter, I don’t think they’re gonna get it,” said Kate. “That doesn’t mean we don’t give our best, but what people seem to like about us is our kind of simplicity, and that’s not artificial—it exists.”

As girls, Kate and Anna had been captivated by George du Maurier’s Trilby books, about a young model taught to sing by Svengali, the manipulative and exploitative mind controller whose name became a music-industry boogeyman. The idea of contorting oneself for success couldn’t have been further from how Frank and Gaby raised their daughters to joyfully embody their experiences through song. (Frank died before their debut was released, and the album was dedicated to “the coach on the piano bench who would have been happy to see his girls get so far.”) The McGarrigle sisters made music for living, rather than living for music. Their unwavering stance would produce several decades’ worth of rare, beautiful albums documenting their idiosyncratic family life. The steadfast, singular heartsong of Kate and Anna McGarrigle was the first chapter in its gospel.

Additional research by Deirdre McCabe Nolan.

https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/kate-and-anna-mcgarrigle-kate-and-anna-mcgarrigle/

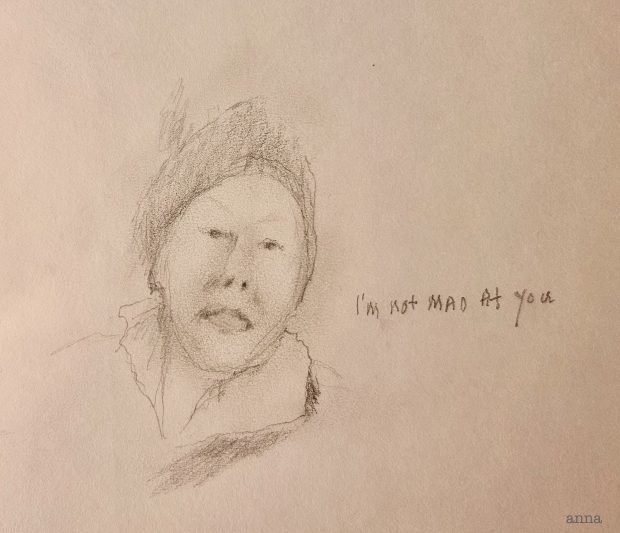

5 Comments »the tunnel of love is cold and lonely

pic by Lily A Lanken

pic by Lily A Lanken

Bon voyage, Jane

Born: April 26, 1941 in Montreal

Died: January 24, 2025 in Montreal

Laury Jane McGarrigle, Mountain City Girl

From a youth playing organ at the funerals of Polish aristocrats, to a stint in the Bay Area during the birth of the internet, to a carnival ride as a collaborator with her little sisters, Jane McGarrigle’s life as a writer, a businesswoman, and a musician, was big and full of adventures.

The first of three daughters born to Gabrielle Latremouille and her husband Frank McGarrigle, Jane was born in Montreal, but raised in the red-and-white house her father built in the Laurentian town of Saint-Sauveur-des-Monts.

Lovingly called “The Duchess” by her doting parents, she learned to play piano and sing harmonies in the family home. Scouted by local nuns, she began her career as the 14-year-old organist at l’Église de Saint-Sauveur-des-Monts, where her propensity for playing Great Balls of Fire on the church organ gave the first hints of both the extraordinary musical ability and the rock-and-roll attitude that would define her.

A few years after skirting expulsion from boarding school at Combermere for her overplaying of Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” she married David Dow in Montreal. Together they hit the road, racing their MGB in sports car rallies, setting up life in Fredericton, NB, and ultimately heading west, crossing the Rocky Mountains and moving to San Francisco in 1964.

With a knack for turning the everyday into an adventure, she reveled in the heyday of counter culture there, nurturing many lifelong friendships at happy hours, après-ski, beach excursions and be-ins and riding their motorcycle to the infamous Rolling Stones concert at Altamont. Settling down, she and Dave had a couple of children, while Janie continued writing music and playing piano gigs with local artists such as Dick Oxtot’s Golden Age Jazz Band.

She had an exceptional love for California and maintained her connection to it for the rest of her life. The couple moved about pretty California with their young family, eventually winding up in the Lake Tahoe area. In 1979, Janie felt the pull of Montreal and returned to her McGarrigle family. Back in Montreal, she was a regular on the Main, managing her now successful kid sisters, Kate & Anna McGarrigle, while joining them on tour and in studio.

In 2015 she and Anna wrote a book about their Laurentian upbringing, “Mountain City Girls,” which the Globe and Mail described as “a non-regretting, red-wine read full of anecdotes and antiquity, with the well-turned phrases of a generation who took care of language.”

A rare musician who deeply understood the complexities of the music business, Janie was a friend to many the singer, picker and player on the dusty road, and spent two decades managing artists, serving as a board member of the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada (SOCAN) where she defended publishing rights for musical authors. Most recently, she played dobro and piano with her partner Peter and their band, The What Four, while fighting off the heartless beast that is ovarian cancer.

Jane is survived by her children, Anna Catherine Dow (Robert McMillan), Ian Vincent Dow (Kathleen Weldon); her grandchildren, Gabrielle McMillan, Islay McMillan, Anna Sophia “Fifi” Dow; her cherished sister, Anna McGarrigle; much-adored Carmichael, Wainwright, and Lanken nieces & nephews, and her sweetheart, Peter Weldon.

Heartfelt thanks to the extraordinary Gynecologic Oncology team at the JGH Segal Cancer Centre. A special thank you to Drs. Gottlieb, Salvador, and Lau, whose expertise, dedication, and compassionate care kept Jane alive and thriving. We will forever be grateful for their care.

Halloween/Edgar Allan Poe

The Season of Edgar Allan Poe: Autumn, Halloween and The Falling Darkness / from the Library of Congress

October 7, 2024

Posted by: Neely Tucker

Edgar Allan Poe died 175 years ago today, Oct. 7, 1849, in a Baltimore hospital under circumstances that no one has ever fully understood.

He was en route from speaking engagements in Virginia to New York when he went missing in Baltimore. After several days, he was found the night of Oct. 3, the day of a local election, lying outside a pub that doubled as a voting precinct. He could barely speak, apparently had been beaten and was wearing shabby clothes that were not his. There have been endless theories about he came to be found in this state, from rabies to a brain tumor to severe alcoholism. Many historians say it’s most likely that he was the victim of cooping, a brutal form of voting fraud in which victims were violently forced to impersonate legitimate voters at the polls, oftentimes with liberal amounts of alcohol involved.

In any event, Poe lingered for four days in a windowless hospital room, never regaining coherence. He died at 5 a.m. on Oct. 7. He was 40.

Among his literary masterpieces was “The Raven,” which began with one of the most famous lines in American poetry: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary…”

Though Poe and the poem are now closely linked with his sometimes home and burial place of Baltimore (the titular bird is now the mascot for the city’s NFL franchise), he was born in Boston and educated as a youth in England and the poem was written in New York. It first appeared in the New York Evening Mirror on Jan. 29, 1845. It was buried on an inside page amid ads for lamps and sheet music.

Poe spent a lot of time thinking about burying things (like tell-tale hearts), but this particular newspaper copy was headed for immortality.

“The Raven,” the dark tale of a grieving young lover encountering a black bird with a fiery stare and a one-word vocabulary, is one of the most anthologized and instantly recognizable poems in American history.

The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division preserves an original copy of the Evening Mirror that day, marking the moment the poem entered the national culture.

It was clearly inspired by Poe’s tragic circumstances.

Poe and his first cousin, Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe, had married in 1836, when she was 13 and he was 27. There has been much speculation about their relationship (even for the era, she was extremely young to be married) but the pair seemed devoted. Her adoring letters refer to him as Eddie.

The couple was struggling to get by on the earnings from Poe’s literary career when, in 1842, Virginia contracted tuberculosis. She was just 18. It was a slow and terrible way to die — as the bacterial infection spread in the lungs, it caused bloody coughs, chills, fever, weight loss and night sweats. As the years ground on, the disease waxed and waned. Poe, already possessed of a macabre imagination and often debilitated by alcohol, later described the period this way: “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

It was during this terrible period that he wrote “The Raven.” He seemed to be anticipating, with great dread, the depression that would crush him after Virginia’s death:

“Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.”

He published it in January 1845, with the bird’s resounding refrain of “Nevermore” becoming a sensation. The editors at the Evening Mirror considered its remarkable gothic nature, haunting phrases, perfect meter and recognized genius: “It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it,” the paper wrote.

In an essay published the next year, “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe uses the poem as an example of his work method. He never mentions Virginia’s impending death as an influence, but late in the essay he does explain the poem’s dark power.

The first part of the poem is straightforward, he wrote. The beautiful Lenore has died. Her grieving suitor is reading late one night, trying to fend off his grief. A raven raps at the window and flies in when it is opened. The narrator, more bemused than alarmed, reasons that the bird has escaped its owner, happened by his illuminated window late at night and sought refuge. It can mimic speech, like a parrot, but knows only one word: “nevermore.”

A little weird, sure, but this is all rational.

But then the narrator reclines on a sofa where Lenore had often lain, resting his head “on the cushion’s velvet lining.” Meant to be a comfort, the soft fabric instead reminds him that Lenore’s cheek had often lain on this exact spot. The shock sends his mind into hallucinations:

“Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose footfalls tinkled on the tufted floor.”

The world has warped — seraphim are celestial creatures, winged angels — and our narrator now believes that he is hearing the footsteps of invisible spirits on the carpet all around him.

Now things turn brutal. The narrator knows perfectly well that the bird can only say “Nevermore,” but he begins to ask it hopeful questions — Is there spiritual help for his pain? Will he and Lenore be reunited in the afterlife?

“Nevermore,” thunders the bird, lashing him with the pain he wanted. This is a sort of perverse masochism, Poe writes in the essay, as the narrator is impelled by “the human thirst for self torture.” The more pain, the more he likes it: “…he experiences a frenzied pleasure in so modeling his questions as to receive from the expected ‘Nevermore’ the most delicious because the most intolerable of sorrow.”

Then, just when we think it’s all over, Poe drives in the dagger.

In the last stanza, he changes the tense from past to present, from a night in the past (“.. it was a night in bleak December”) to the horrifying present. The narrator hasn’t been remembering a quaint evening of yore, but is reporting from right now and … the raven is still there. We have no idea of how much time has passed, but we get the idea it is considerable because the narrator says “still” twice. There are no more whiffs of invisible angels, only the glare of a demon’s eye:

“And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,”

The bird, we know now, will never leave. There is no balm in Gilead. There is no escape from grief. The last use of the word “Nevermore,” Poe wrote, “should involve the utmost conceivable amount of sorrow and despair.”

Virigina died two years and one day after “The Raven” was published. While her corpse lay on the deathbed, Poe had an artist paint her portrait. It is the only image of her known to still exist.

In life, as in “The Raven,” Poe never seemed to fully escape his grief. He was sometimes found after dark in the years to come, sitting beside her grave. His last completed poem was “Annabel Lee,” in which the unnamed narrator is haunted, much like the protagonist of “The Raven,” by the death of his beautiful young love. At the poem’s conclusion, the narrator pictures climbing into the tomb with her corpse:

“And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.”

Autumn is Poe’s season, the time of year when his dark, dazzling works seem to most come to life. Halloween still seems like a holiday he would have created if hadn’t already existed; the long night, the ghosts, the fears of The Thing in the Dark. And finally, there is the everlasting sense of horror from the last lines of “The Raven” — there will never be any solace from the grave; only the dark, deep, terrible silence.

Happy Halloween

2 Comments »