i am become wood

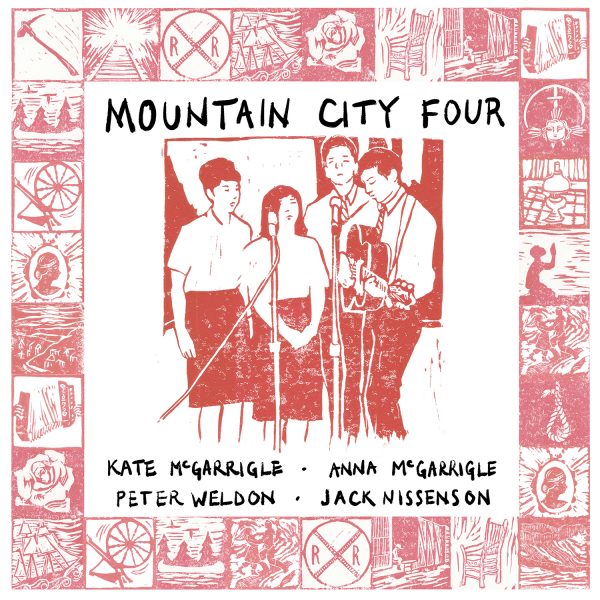

And while I’m at it, downloads of these two Kate & Anna recordings are available at

https://la-tribu-disques-et-spectacles.myshopify.com/search?q=mcgarrigle

4 Comments »

https://omnivorerecordings.com/shop/mountain-city-four/

5 Comments »Thanks Joel Z for finding this.

SHUT YOUR MOUTH HÉLÈNE

….‘Keep your pecker in your pocket, Paddy,’ Jacques Aubry says, pointing at Mrs. Boyle’s swollen front, ‘and you’ll have less need for marching.’

By Nuala O’Connor

The walking makes yellow blisters erupt on Hélène’s feet. Primrose-colored sacs of liquid, rimmed with scarlet. She bursts them at the campfire by night, after easing out of the boots that seem to shrink around her feet the farther she walks. She does not complain to Maman or Papa, she knows what they will say: Ferme ta gueule, Hélène. Hush! You are ten. Think of Ti-Pit and Ti-Jean—they are small boys. Do you hear them grouse? It has been said more than once to her already.

All day they walk, a group of twenty, between adults and children, with one wagon for belongings, as well as a few horses and mules. The Connecticut River—and, later, the Merrimac—sparkles and spates beside them, a lure for Hélène’s ruined toes and heels. She keeps her head turned to the water and imagines sitting on the bank to paddle her feet. She wishes she could swim naked as a trout through the river, the way she does in the Chaudière, with the chutes crashing above her like a million liquid angels tossed from on high. How she loves to bathe and dive in that river pool below the falls. She misses her home in Lac-Mégantic; she misses Grandmère and her friends and the schoolroom. Yes, she even misses the chickens and sows who cause her so much bother with their greedy peck-and-snuffle.

‘Does New Hampshire have a school, Maman?’ Hélène catches up with her mother and walks beside her. She will talk to her as a way to unbalance the hunger pains that claw at her belly.

‘It has schools, petite, but you will not see the inside of one, as you well know.’

Hélène pouts her lip. ‘What will I be doing, Maman?’

‘Whatever is asked of you. You’ll carry water, darn clothing, knit, spin. Any chore that needs to be done.’

‘I want to go to school. I miss my books.’

‘Ferme ta gueule, Hélène! I have enough on my mind without listening to nonsense. You know you are not to speak unless you have something useful to say.’

‘Désolée, Maman. Sorry.’

‘Walk with your brothers.’

Every night at the campfire, Paddy Boyle sings sad songs. Hélène does not need to understand Gaelic to know that the songs are mournful—the tunes soar and drop in such melancholic waves, and his wife’s tears flow so freely, it is clear the verses are full of sorrow. By day, Mr. Boyle is an angry man. He beats the mules and snaps at Hélène because she walks too close ahead of him when she is mesmerized by the river’s torrents that sing to her like sirens.

‘Get out from under me feet,’ he bawls, making Hélène jump like a scalded rat. His huge boot comes scraping down her calf because she has dawdled too long in his path again. He yells at Maman, ‘Missus, can you not rein in that child? She’s away with the fairies half the day.’

Other times Hélène catches him looking at her, his tongue poked from the corner of his mouth, a furtive smile prowling his lips.

Mrs. Boyle—Kitty—is a toad of a woman, wide of hip and flat of face. Her hair is cut short and Hélène doesn’t dare ask Maman why. Mrs. Boyle rides the wagon, perched on the back with her legs a-dangle, because she is with child. It seems to Hélène she sits there in judgment over them all.

One afternoon she comes upon Mrs. Boyle kneeling by the bank of the Merrimac, praying aloud. Hélène likes the guttural, raw sound of the words: ‘Go dtaga do ríocht, go ndeintear do thoil…’ It is a language that seems to be scraped up from the speaker’s gut before being delivered to the tongue.

Mrs. Boyle’s bonnet is on the grass beside her and Hélène sees the shorn head and also whorls of scabby scalp where hair is missing. It disgusts the girl but she feels sympathy too, for what is a woman without bountiful hair? Kitty Boyle snatches up her hat and shoves it on her head when she realizes she is no longer alone.

‘Oh, it’s only you,’ she says, looking at Hélène. She ties her bonnet strings and attempts to get up. Hélène goes to her and allows herself to be used as a prop. Mrs. Boyle leans heavily on her to get her footing, her breath falling on the girl’s face; Hélène is surprised to find it sweet, like Saskatoon berries.

‘Mo bhuíochas,’ Kitty Boyle says. ‘I thank you.’

‘Muh vweekus,’ Hélène mimics, and they smile at each other.

‘Merci beaucoup!’ Mrs. Boyle says, giggling a little at her pronunciation and looking to Hélène for reassurance.

‘De rien,’ she answers.

They walk back to where the others sit, alone and in groups, drinking from water cans and biting into hardtack. Hélène’s papa gives the signal—a short blasting whistle through the teeth—and everyone rises, both keen and reluctant to begin walking again. The sooner they move, the sooner they might come upon a farm to buy eggs and milk. The sooner they eat well, the quicker they will gain the mills of Nashua, New Hampshire and the promised work. Then there will be money, clumps of it.

‘Nearly two weeks,’ says Mr. Boyle, ‘marching like savages.’

‘Keep your pecker in your pocket, Paddy,’ Jacques Aubry says, pointing at Mrs. Boyle’s swollen front, ‘and you’ll have less need for marching. Fewer mouths to feed.’

At first, Mr. Boyle looks like he will thump Jacques, but instead he lets a great, raucous whoop and laughs for longer than is needed. Hélène looks at Kitty Boyle, enthroned once more on the back of the wagon, but her face stays rigid, as if she has not heard anything that has passed between her husband and Jacques Aubry.

* * *

The moon slithers up over the trees, a silver coin against the navy sky; stars hang in milky drapes. Hélène could spend her whole life watching the variance of the skies and be content doing it. She means to stay awake until dawn, to follow the moon’s chase of the sun, but she falls asleep. Morning fingers its way up, dragging its fleshy caul, and the night-spell is fractured. Maman heaves herself towards the campfire and pokes at the embers, sending up ash in clouds.

Hélène takes the pail to the river and dips it low for water, lying on her front so she can pull it up by the handle with both hands. A movement makes her look into the river where she is astonished to see Kitty Boyle rise out of the water before her like an apparition. Hélène drops the pail into the river and has to scramble after it; she grabs it before it sinks and stares at Mrs. Boyle, who is dressed only in her underthings. The material clings to her body, clearly showing the dark parts of her breasts and the swell of her stomach where Hélène knows a babe wriggles. She stands in the water and lifts her arms as if she means to flop backwards and sail away.

‘Mrs. Boyle!’ Hélène calls. ‘Kitty!’

The woman focuses her gaze and lowers her arms; she starts to wade towards the bank. ‘I’d be gone but for you came,’ she says.

Hélène slips into the Merrimac and hauls Kitty out, half pulling, half shoving her. The woman seems not to want to leave the river, though it is cold. Pushing her onto the bank, Hélène squats and wraps her own shawl around Kitty’s shoulders.

Mrs. Boyle bows her head and says, ‘I’m all right now, a leana.’

Hélène is not sure if she is speaking to her, or the baby that grows inside her belly.

‘Where is your gown? Your shoes?’

Kitty Boyle points to a stand of bushes and Hélène fetches her clothes. She pulls them on over the woman’s wet skin and undergarments, dressing her as if she is an enormous doll.

‘Will you tell?’

Hélène looks at Kitty. ‘I know to keep my mouth shut.’

She shivers and nods her thanks.

* * *

Hélène uses Kitty’s mallet to pin down the Boyles’ tent. Kitty stands with her hands tucked into the arch of her back, letting Hélène take over this small job from her. The girl is happy to help, happy to relieve her new friend of some of her tasks. Thwack goes the mallet, deep goes the pin.

Mrs. Boyle teaches Hélène how to knit in the Irish way. Her cables and diamonds do not look as firm and flowing as they should, but the older woman praises Hélène’s effort before making her rip it all back and start afresh. They sit on the back of the wagon together in the evenings, their needles clacking companionably. Kitty tells Hélène about her island home in the East Atlantic; Hélène tells her about Lac-Mégantic and the river and lake she loves so well.

Paddy stands by the campfire puffing on his pipe.

‘Have I two wives now, hah?’ he says. ‘With ye both at it, I’ll be wearing a new gansey in no time. No time at all.’ Kitty and Hélène raise their eyes to him but do not speak; they continue with their work, the rough wool piled in their laps. Paddy points with his pipe at Hélène. ‘You’ll get nowhere in life without proper schooling.’ He stares at the pair for a moment, spits into the campfire and walks away.

Maman calls Hélène to help her wash pots and plates. Hélène leaves down her knitting and goes to her. They carry the utensils to the river and dip them in, scraping at them with clumps of grass.

‘Don’t be making up to the Boyles. They’re not our kind.’

‘They’re here with us.’

‘He’s an agitator. A troublemaker. Keep away from them.’

‘But, Maman…’

‘Hélène!’ Maman slaps two tin plates together. ‘Ferme ta gueule.’

* * *

The sun is a bright roundel in the sky but the camp sleeps on. Paddy Boyle passed around a few bottles the night before. They held something clear and potent that made Papa gasp when he slugged, but it unfastened his tongue. All the adults drank from the bottles and they sang, laughed and talked late into the night. Hélène tried to stay awake but tiredness from walking all day and the high heat from the banked-up fire made her drowse away, the voices around her becoming liquid and slow.

Now she knows the sun’s late morning heat will have warmed the waters of the Merrimac. She slips down to the bank, undresses to her skin and slides in. The river is still cool, yes, but its chill is friendly somehow, welcoming. A few strokes and she is clear of the weedy tangle of the riverbank; the current is gentle for it hasn’t rained for a while. Hélène swims a bit, lets the water bubble over her mouth, flips onto her back and floats. She closes her eyes and lets the sun beat down on her face and body. She swims and drifts, eyes closed when she rides on her back. In her mind she is in the river-pool of the Chaudière, bobbing towards the spray of the falls; any moment she will feel the first spritz on her face. Opening her eyes, Hélène sees that Paddy Boyle is above her on the riverbank, watching. He flips his suspenders down over his arms and fumbles with the buttons of his trousers. His hand disappears inside his drawers and he starts to beat himself rhythmically. His head jerks backwards and his mouth goes slack but he keeps his eyes fixed on Hélène. She bobs down to tread water and looks up at him. Over the sloshing of the river, she can hear him grunt.

‘Come here,’ he calls. Hélène shakes her head. ‘Come on, now,’ he croons, stretching one hand to her while the other continues to work steadily at himself.

Hélène swims downstream, looking for a sheltered spot where she can climb out and get to her clothes. Paddy Boyle follows her with his eyes and doesn’t notice the approach of Kitty or the mallet that she swings into his stomach. Paddy groans, pitches forward and falls face-first into the dirt. Kitty drops to her knees beside him, raises the mallet and brings it down onto the back of his head. The noise it makes is like the splinter of axe through wood. Kitty shoves her husband along the ground until he dangles over the riverbank. Hélène crouches in the water and looks up at her friend; Kitty stares back. She pants a little but she is as composed as a woman going about the keeping of her house. Kitty glances around, gives a sharp nod and Hélène wades forward and pulls Mr Boyle’s body into the water. His face looms close to hers and she flinches and pushes him away. She and Kitty watch the Merrimac take Paddy Boyle with it, like a piece of driftwood.

Kitty offers Hélène her hand and the girl climbs from the water, sliding on the muddy bank. Mrs. Boyle takes Hélène’s pantalettes from the pile of clothes and helps her step into them. She pulls her gown over her head and fixes the sleeves as best she can over the girl’s wet skin; she takes Hélène’s hands in hers and stares into her eyes. Kitty does not speak but Hélène can hear her.

She nods to say she has understood and whispers, ‘Ferme ta gueule, Hélène. Ferme ta gueule.’

Nuala O’Connor

Nuala O’Connor is an award-winning short story writer, poet, and novelist in her native Ireland. She made her US debut in Miss Emily a reimagining of the private life of Emily Dickinson, one of America’s most beloved poets, through her own voice and through the eyes of her family’s Irish maid. Nuala has won many awards including RTÉ radio’s Francis MacManus Award, the Cúirt New Writing Prize, the Jane Geske Award (USA), the inaugural Jonathan Swift Award and the Cecil Day Lewis Award. She was shortlisted for the European Prize for Literature. She lives in Galway, Ireland, with her family.

http://www.nualanichonchuir.com

Photo taken by Randy Saharuni in 1980 prior to release of French Record (aka Entre Lajeunesse et la sagesse.) At that point Excursion à Venise was the working title of the disk. Randy found a warehouse where they drydocked the old gondolas from Expo 67 and took some shots of the two of us sitting in one. They were a bit daft. This is an alternate.